DIY Culinary Science: Tips, Strategies, & Resources

Measuring the Effects of Applying Force to Baking Cookies

If I were Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos or Bill Gates, I might very well set aside the pursuit of Twitter reformation, space exploration, and worldwide vaccination in place of global dissemination of Culinary Science education. (Wait—am I starting to sound like Jesse Jackson?) I honestly think it’s that important. Knowing how to cook is the first defense against food insecurity. And knowing the science that drives cooking gives you the ability to cook what’s on sale, what’s in the fridge, or what’s in season.

During the pandemic, our dearly beloved governing bodies stepped in to make sure that little mouths didn’t go unfilled for want of a school cafeteria. And I’m truly glad they did because being hungry is no fun. Especially if you’re a kid. But when I saw the packages of Froot Loops, Lunchables, Little Debbies, and Cheez-Its being dropped off by school buses making their rounds, I couldn’t help but think that we could do better. Don’t get me wrong. I like that kind of food now and then. But it’s nothing to live off of.

I’m not a high-powered gazillionaire, and there really aren’t that many people who care what I think. But there are a few, so I’ll start there.

If it is within your power, you should be teaching your children Culinary Science. There. I said it.

Barring anything wildly out of the ordinary, they are going to eat just about every day of their lives. And somebody is going to prepare that food, whether it’s Mom, Dad, McDonald’s, or the factory workers at Chef Boyardee (a Conagra brand.) And in all likelihood, they will also study science for several years in a row. What better way to demonstrate the practical application of science? What better avenue to teach a vital life skill? Is it just me, or is this a match made in Heaven?

With that in mind, I’d like to share some of the strategies, resources, and philosophies that have fueled the development of Inquisicook. Yes, we would love to be the ones to teach Culinary Science to your students, but if it’s not the right time or not a good fit, you can absolutely do this on your own. Scout’s honor.

The internet has all the science info you need. This is an area in which people and organizations share information generously, and in a format that’s easy to access and easy to translate to classroom applications. Just search the keywords/phrases and you’ll see. And if you still want more, there are lots of books on the subject that you can probably get at the library. (Take a look at our recommended resources below.) The real trick is narrowing down the content to something manageable. Here are some recommendations for reining in the possibilities so you can focus on something doable.

Start with the familiar.

Conduct a forensic analysis of a cooking disappointment. Why is my meatloaf so dry and tough? What is that white, gelatinous stuff that leaches out of baked salmon? Why is the first pancake always messed up?

Take a tour of your pantry and fridge and consider what questions you might ask if you were an investigative reporter. Why do pickles last so much longer than cucumbers? Why are some salad dressings always ready to pour while others have to be shaken? What causes bread to go stale, and how can that be reversed?

Consider how you might create the perfect version of a favorite dish. If you want a chocolate chip cookie that’s chewy (not crunchy), dense (not fluffy), golden brown (not pale), loaded with mix-ins (not skimpy), and bodacious in size (not scrawny)—-how might you accomplish that? Or you could reverse any or all of those factors, depending on what YOU like in a cookie. There are so many variables that influence cookie results (choice of fat, sugar, flour, inclusions, chilling time, scoop size, type of pan, baking temperature) . . . you could experiment for weeks.

Local vs. Long Haul Strawberries

Go with the seasons.

Syncing up with the agricultural or holiday calendar is a natural way to work through exploration topics.

Spring/Summer/Fall Garden Produce

Strawberry Science in May

Blueberry Science in June

Apple Science in October

Chocolate Science for Valentine’s Day

Potato Science for St. Patrick’s Day

Boiled/Deviled/Dyed Egg Science for Easter

Engineering the Perfect Taco for Cinco de Mayo

And with all the baking and roasting and saucing that goes on from Thanksgiving to Christmas, the holiday season could be a Culinary Science boot camp in itself.

Once you get your topics narrowed down, it’s time to think about the teaching process.

Build good habits right from the start.

Teach good kitchen health and safety practices. Little things like turning pot handles inward or wiping up spills immediately can prevent serious injury, and learning to handle raw poultry safely should be a prerequisite to cooking with it.

Teach precision and care in the kitchen. Have students wait until the oven is completely preheated before adding a dish. Ask them to measure ingredients instead of guesstimating. Set a timer for timed processes.

Have them clean up their own messes, and expect them to do it well. If you have to rewash the cookie sheet because the back side is still greasy, take the time to teach them to do the job more thoroughly.

Embrace Mise en Place. This is a French term that means “put in place,” and it rhymes with “trees on moss.” First, have them do all the preliminary prep work (shredding, chopping, grinding, melting, washing produce, etc.) Then they should measure out all the ingredients and arrange them in the order they will be used. Finally, it’s time to gather all the tools and equipment they’ll need.

Mise en place makes the difference between a frazzled, distracted cook and one who is calm, clear-headed, and having a good time. Advance preparation makes it much less likely that they’ll measure incorrectly, accidentally grab baking soda instead of baking powder, or be caught without a spatula at the exact moment the egg needs to be flipped. The investment they make in setting things up will free their minds and hands to be completely involved in the cooking process. The only thing it costs is a few extra dishes to wash. It’s a small price to pay.

Molecular Model of Egg Foam Formation

Choose the methods that make sense for your students.

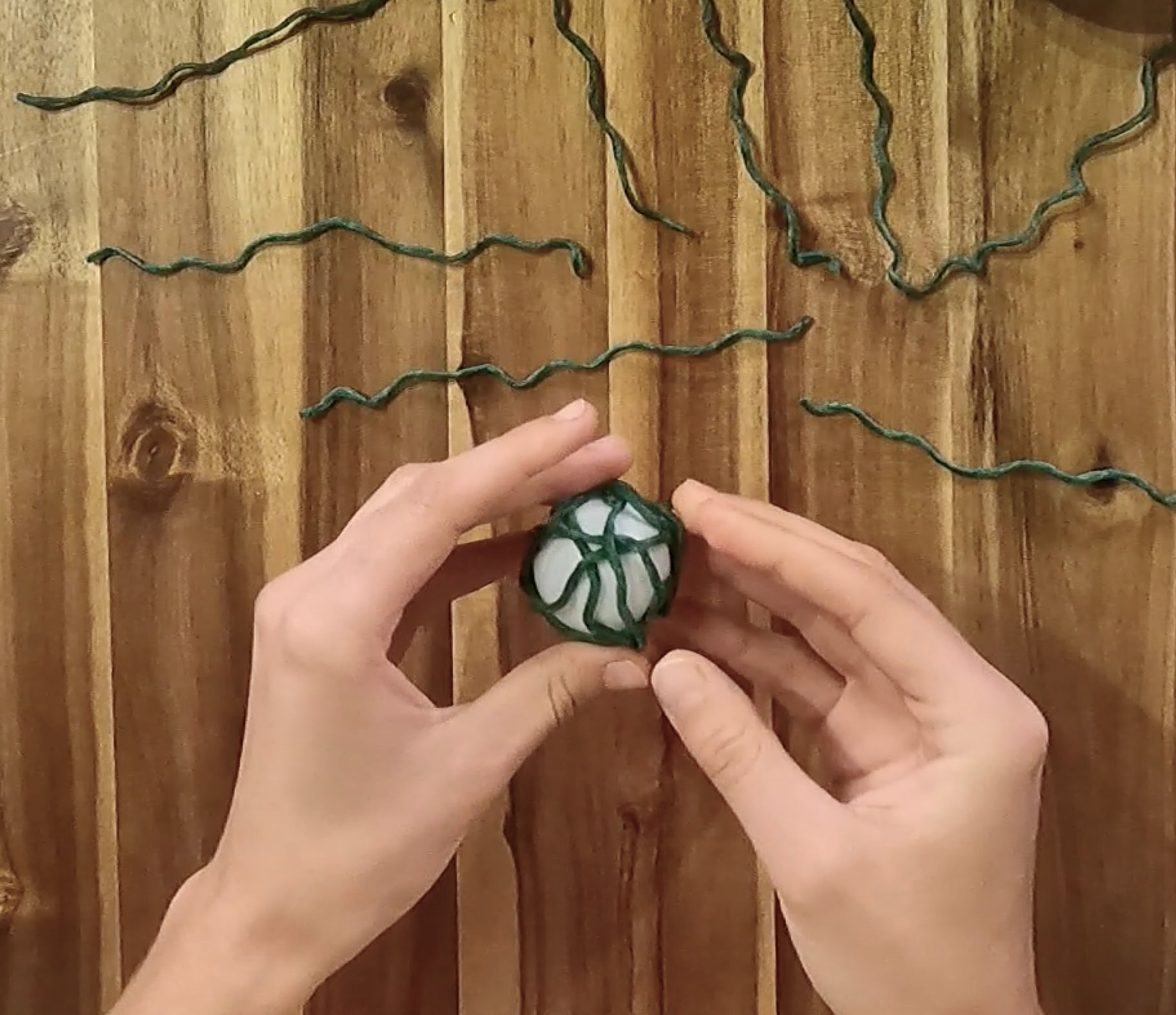

Inquisicook uses scientific modeling extensively because it gives abstract concepts concrete representation. It also adds a fun, hands-on activity to the mix. Any time your resources show illustrations of microscopic components or phenomena, ask yourself if it might make a good model. For instance, you can use Play-Doh to model the yeast reproduction process, called budding. And with a little imagination, you can make several different versions of edible plant cell models with some gelatin and a trip down the produce aisle.

We also rely heavily on narration to improve student retention. Having to explain the details of something you’ve learned in your own words forces you to think it through until you really get it. It also gives the parent a chance to clear up anything that may have been misunderstood.

Blind taste tests are exciting and enlightening. Preparing multiple versions of a dish and comparing them side by side almost feels like a game show, and it teaches students to focus on the nuanced differences.

Sensory evaluation is the process of analyzing prepared food on the basis of appearance, flavor, texture, and aroma. It trains students to think about results with specificity and gives them a road map for crafting improvements. Inquisicook students are asked to conduct a sensory evaluation of almost all the recipes they prepare.

Quizzes and tests are easy to put together, and they up the ante on committing essential information to memory.

Of course, experiments are a key component of science. My first word of caution is to avoid playing fast and loose with what an experiment is. Slicing an apple and leaving it on the counter to see what happens doesn’t count. Experiments involve observations/questions, hypotheses, methods, evaluations, and conclusions. Even little kids can be gently introduced to this process by asking the right questions. “What have you noticed about apples after they’re sliced? What do you think this apple will look like in two hours? Do you think brushing some of the slices with honey water will make a difference? What about lemon water?”

Comparing the efficacy of whipped cream stabilizers.

Now that you’ve got them thinking like a scientist, it’s time to have them act like a scientist.

Manage samples wisely. Using eggs from the same carton, flour from the same bag, and blueberries from the same container minimizes quality differences that could make the results unreliable.

Use a control when appropriate. A control is a sample that has not been changed in any way. It’s used as the standard for other samples to be compared against.

Only change one variable at a time. They can repeat the experiment with additional changes later if they like. For instance, if they’re exploring how cookies are altered when substituting shortening or oil for butter, only change the fat. Now is not the time to also switch to a different kind of flour or substitute brown sugar for white sugar.

Measure accurately. Whether they’re keeping track of time, measuring ingredients, or monitoring temperatures, have them be as precise as possible.

Train them to write clear notes, take pictures or draw diagrams, and concisely explain what the results mean. If they keep everything well organized and they’ll be able to use the information for years to come.

Still Life with Apples by Paul Cézanne, c. 1890

Opportunities for learning extensions abound in the world of Culinary Science, and they’re good for keeping kids who aren’t big on science or cooking engaged in the process. Look for ways to draw in elements of food anthropology, science history, literature, art, or pop culture. If you have enough content, you can put together an entire unit study. For instance, if you want to study apple science, you could also learn about Johnny Appleseed, the legend of William Tell, the Golden Apples of the Hesperides, the poem “After Apple Picking” by Robert Frost, Paul Cézanne’s “Still Life with Apples,” or the origin of the Beatles’ record label.

Now for some recommended resources. Since it sometimes feels like the www of the world wide web really stands for the wild, wild west, I’ll start with a few online sources.

Almost every commodity food product has a national organization that promotes its interest. The American Egg Board, National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, and The Popcorn Board are just a few examples. These sites offer things like infographics, recipes, coloring books, fun facts, and sometimes complete lesson packages that are absolutely free.

Major manufacturers’ websites can also be rich sources of free Culinary Science information, and don’t forget to check out their YouTube channels.

Dedicated sites like Compound Interest and Food Crumbles serve up ready-to-use information that’s a little more complex, but it can be adapted for use at lower levels.

We use a pretty extensive library of food science and culinary arts books in our research, but a few stand out as good options for home use. Many of them are widely available at public libraries. Note: We do not participate in affiliate programs and we do not make money off of your clicks. The links are provided for your convenience.

4-H Curriculum What’s on Your Plate?

I’m Just Here For The Food by Alton Brown (see also Good Eats episodes)

Bakewise by Shirley Corriher (see also Cookwise and Kitchenwise)

I realize I’ve loaded your plate with quite a bit of information, but hopefully, you can see that self-styled Culinary Science is within reach. If it all sounds good but you’d rather outsource the teaching, we’ve got you covered with our Inquisicook course options. If you’ve been inspired and empowered by this post, share it with a friend or give us your feedback. We’d love to hear from you!